By August Kruger

Horticulturalist

Agri TechnovationPhysiology Research Center

With higher mean temperatures and the in- creased length of daylight that accompany our seasonal transition from winter to spring, the stage is set for the next important step in annual avocado tree phenology, fruit set, cell division and cell enlargement. Integral physiological processes – the precursor to the coming harvest.

Generally, only a very small number of avocado flowers eventually set fruit. Studies conducted estimate it at barely 0.15%, which translates into approximately 1 fruitlet per every 700 flowers. Also, the starch content of flowers that set was found to be up to 3 times higher than the content in flowers that did not set fruit3.

This highlights the importance of understanding and monitoring tree carbohydrate levels, which has now been made commercially possible through Agri Technovation’s ITEST™ CARBOHYDRATES services.

Fruit set is followed by a phase of rapid cell division lasting between 6 – 8 weeks, after which the cell enlargement phase commences and lasts until fruit reaches around 50% of the final size. Thereafter the fruit size continues to increase through a slower rate of cell division1.

It is important to note that avocado fruit is largely heterotrophic and that their growth de- pends on both the import of photoassimilates from leaves as well as the fruit’s own photosynthesis.

Through previous research conducted on physiological growth models of avocados in subtropical climates similar to South Africa, it was found that the photosynthesis rate peaks during February to April, and plummets to around half of the peak from July through to September. This decreased photosynthetic rate is attributed to photoinhibition due to excess light energy that cannot be utilised under cold temperatures, resulting in the damage of leaf chlorophyl.

Figure 1: Seasonal changes in key leaf parameters

This decreased photosynthesis rate coincides with the critical avocado fruit set period, which is certainly not ideal when considering that flowers and fruit are energy expensive plant organs to maintain.

The importance of stored starch reserves to supplement the energy demand of developing fruit during this critical time, cannot be under- estimated. Foliar nutrient applications provide the means to implement an effective and rapid corrective strategy. Agri Technovation has a wide range of foliar products superiorly formulated for increased uptake and effective action.

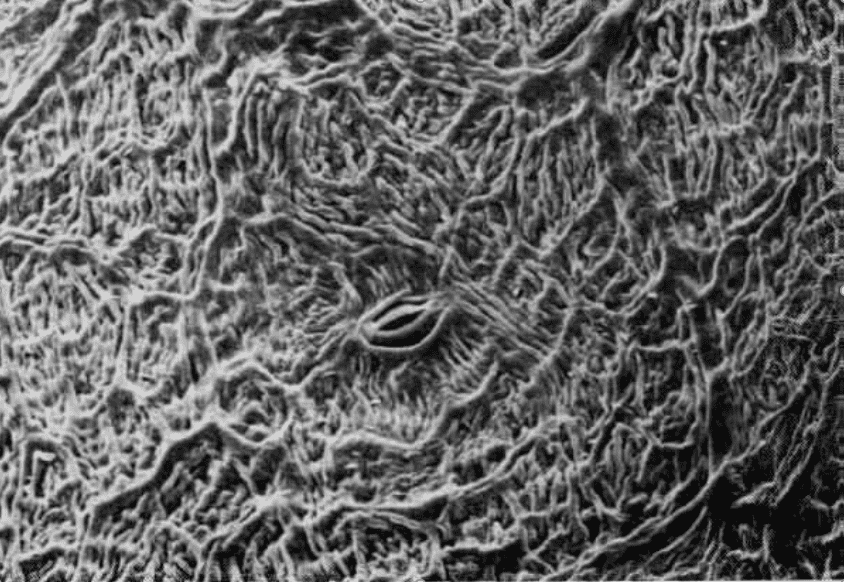

Figure 2: A scanning electron microscope (SEM) photograph illustrating the stomata on the skin of an avocado fruitlet x 440 magnification.

Figure 2: A scanning electron microscope (SEM) photograph illustrating the stomata on the skin of an avocado fruitlet x 440 magnification.

At fruit set, CALCINATOR™ and FLOWER POWER™ will provide calcium and boron for effective cell division.

K PHLOEM™, ZINC PHLOEM™ and MAGNESIUM PHLOEM™ will supplement potassium to facilitate effective transport of sugars to developing fruit, while zinc and magnesium will contribute to ensuring effective photosynthesis through the maintenance of chloroplasts and their effective functioning.

With regards to effective uptake, it must be noted that avocado fruitlets have the highest number of stomata per surface area during the rapid cell division period shortly after fruit set, at 50 to 75 per mm2. Figure 2 above is a scanned electron microscope photo illustrating stomatal guard cells (4). Since stomata are one of the entry pathways for foliar feeds, this pro- vides a unique opportunity for improved uptake of foliar nutrient applications.

Citations:

- Dixon, , Lamond, C. B. & Elmlsy, T. A. (2006), Patterns of Fruit Growth and Fruit Drop Of ‘Hass’ Avocado Trees In The Western Bay Of Plenty, New Zealand. New Zealand Avocado Growers Association Annual Research Report, Vol. 6: 47 – 54.

- Wolstenholme, N., (2011), Understanding the Avocado Tree – Introductory Ecophysiology, ARC Institute for tropical and subtropical crops – Cultivation of Avocado, 35-48.

- Hormanza, (2014) Factors influencing Avocado Fruit Set and Yield. From The Growe, 34 – 36.

- Blanke, M. (1992) Photosynthesis of Avocado fruit. Proc. of Second World Avocado Congress, 179 – 189.